1.1 Background to and Motivation for the Project

An important factor in being able to manage metered water effectively is knowledge of its price elasticity of demand. The need for estimating the price elasticity of demand for water in South Africa was emphasised by representatives of the World Bank during a meeting with the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry to discuss water tariffs during November 1996. So far as is known, no recent research effort has been undertaken into the subject in South Africa, however.

To correct that situation in 1997 a research project was initiated by the Water Research Commission (WRC) to address this problem. The report following this Executive Summary is the result of this initiative.

In studying the literature on determining the price elasticity of demand for water as a consequence of price increases, the researchers undertaking the WRC study found that econometric analysis was the common approach adopted. This approach requires a substantial database for exogenous and endogenous variables; such a database is not readily available to researchers in South Africa in an appropriate form at present. A study undertaken in Australia in 1987, however, approached the problem of estimating the price elasticity of demand for residential water using Contingent Valuation Methodology {CVM)1.

Because of the data acquisition problems envisaged in undertaking the WRC study by means of an econometric analysis, it was decided to follow the Australian approach in the WRC study. This study therefore centres on the estimation of the residential price elasticities of demand for water for different income groups by means of CVM making it a unique initiative so far as South Africa is concerned.

1Thomas, ]F & Syme, G]: Estimating Residential price Elasticity of Demand for water; A Contingent Valuation Approach. Water Resource Research, vol. 24, No II, 1988, pp 1847-1857.

1.2 Research Objective

The objective of this research study is to estimate the residential price elasticities of demand for water for different income groups by means of CVM. In this approach, research to determine the value of goods which are not bought or sold In the market, is undertaken by setting up a situation where respondents are asked in surveys how much of a non-market commodity, in this case water, they would buy as the price increased. Responses to this question are known as "Contingent Values", because they are values respondents perceive they will pay contingent upon a market being created. The literature shows that CV values are good surrogates for actual behaviour and that CV measures from surveys can be directly and validly compared with economic values attained from behaviours in the market place.

This study was undertaken in the residential areas of Alberton and Thokoza, 111 people were interviewed in Alberton and 50 in Thokoza, giving a total sample size of 161.

1.3 Methodological Approach to the Study

The methodological approach to this study was by means of a two-stage interview survey.

- Survey No 1 : Consisted of establishing a water usage profile for different income groups in Alberton and Thokoza.

- Survey No 2: Consisted of a CV experiment and analysis.

The purpose of Survey No 1 was to establish detailed water use characteristics for the areas chosen. This information was necessary in order to be able to undertake the second survey.

The purpose of Survey No 2 was to provide data on consumer responses contingent upon price increases for water, so that the price elasticities of demand could be estimated. In spite of the difficulties expected with respect tp data acquisition, an econometric model was also designed for attempting to cross-check the values found.

1.4 Summary of Results of the Study

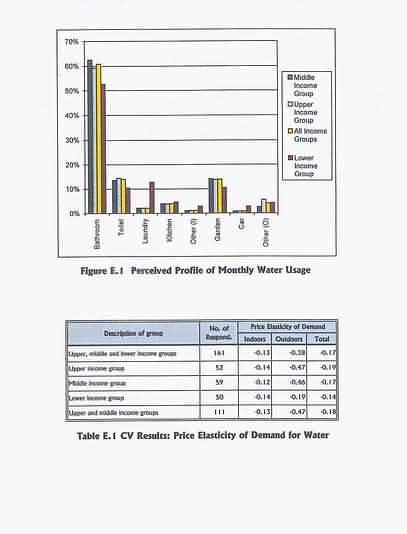

During these surveys, It was found that people were not aware of how they used water, nor were they aware of how they could save water. As a result, It was necessary to undertake an educational programme as part of the complete process In order to arrive at a meaningful result. Surveys 1 and 2 were therefore used In conjunction with each other, and the end result of the analysis yielded defensible estimates of the price elasticity of demand for domestic water usage amongst residential consumers in Alberton and Thokoza. The results obtained from the two surveys are summarised In Figure E.1 and Table E.1 below. From the results It can be seen that the price elasticity of demand for total water usage in Alberton and Thokoza is -0.1 7. It therefore follows that if the price of metered water for residential use is increased by 10%, the total water demand would be reduced by 1.7%.

Whilst the research objective of the study was successfully achieved, unfortunately (and as expected) due to insufficient quality historical data, the econometric model developed for comparison purposes for predicting the short-term price elasticity of demand could not be exercised. An attempt was made, however, to use the econometric model for gauging the long-term price elasticity of demand for water. This was done so that the results could be compared with the only other study found by the researchers for determining the price elasticity of demand for water In South Africa which was that undertaken by J A Döckel2. In this study Döckel used a macro-econometric model to determine the long-term price elasticity of demand for residential water in an area that is now greater Gauteng, some 25 years ago. Döckel's research yielded a price elasticity of demand of -0.69 which compares favourably with the figure arrived at from the macro-econometric model used at Alberton which yielded a figure of -0.73.

2 J.A. Döckel: The Influence of the Price of Water on Certain Water Demand Categories, Agrekon, volume 12, No.3, July 1973.

1.5 Conclusions Drawn from the Study

The CVM used in this study has been found to be a powerful approach for determining the price elasticity of demand for water. T o demonstrate this, comparisons are now made between the results of the research carried out in this study and the results of international research undertaken to determine the price elasticity of demand for water. For ease of comparison the following two tables are used:

- Table E.2 below compares the price elasticity of demand for total water usage in the short-run in various international studies. All of these international studies, except for the last two in Table E.2, have used a macro-economic approach for determining the price elasticity of demand.

- Table E.3 below compares the short-run price elasticities of demand for indoor, outdoor and total water usage found in this study with the study carried out in Perth, Australia referred to above. These comparisons are of course particularly important since as noted already, both studies were carried out using CVM.

Researcher/s

Date

Location

Price Elasticity

Carver and Boland

1969

Washington D.C.

-0,1

Agthee and Billings

1974

Tucson, Arizona

-0,18

Martin et al

1976

Tucson, Arizona

-0,26

Hanke and de Mare

1971

Malmo, Sweden

-0,15

Gallagher et al

1972/3 & 1976/7

Toowoonba, Queensland

-0,26

Boistard

1985

France

-0,17

Thomas and Syme

1979

Perth, Australia.

0,18

Veck and Bill3

1998

Alberton & Thokoza, South Africa

-0,17

Table E.2 Comparison of Short-Run Price Elasticities for Total Water Usage4

Researchers

Date

Location

Price Elasticity

Indoor

Outdoor

Total

Thomas and Syme

1979

Perth, Australia

-0,04

-0,31

-0,18

Veck and Bill3

1998

Alberton & Thokoza, South Africa

-0,13

-0,38

-0,17

Table E.3 Comparison of Short-Run Price Elasticities for Indoor, Outdoor and Total Water Usage

3 Of Economic Project Evaluation (Pty} Ltd (EPE}

4 CV methods were undertaken by Thomas and Syme and Veck and Bill, the remaining studies used short- term macro- econometric methods.It is important to emphasise that the figures quoted in the tables above are all short-run price elasticities of demand for water. It is clear that the results are very compatible in both tables. It will be observed from table E.2, in the international case studies, the price elasticities of demand for total water usage range from -0.1 to -0.26. The literature reports short-run average price elasticities of demand for several international studies to be -0.21 as against -0.17 found in this study. This gives considerable confidence in the figures obtained from this study.

Table E.3 offers a comparison between this study and the Australia study referred to above, i.e. comparing both the indoor, outdoor and total price elasticities of demand for water. The method of approach in these two studies is also directly comparable, as is the range of the price increase considered. In addition, different levels of income were also considered in both these studies. The price elasticity of demand for indoor water use in Perth is seen to be more inelastic compared to this study, whereas the outdoor elasticity is very comparable, i.e. -0.31 in Perth and -0.38 in Alberton/Thokoza. It is suggested that the large difference in the indoor price elasticity of demand for water between Perth and Alberton/Thokoza Is as a result of a better understanding that water consumers In Perth have of the scarcity value of water. This understanding arising from an extensive educational initiative that was undertaken after the severe drought in Perth which occurred in the late 1970's prior to the Australian study being undertaken.

In comparing long-run price elasticities of demand with those in the short-run as determined in this study it is seen that in the long-run, the price elasticity of demand for water is more elastic than in the short-run. For example the average short-run price elasticity of demand for water is -0,21, whilst in the long-run, the average figure is -0.6. This difference is generally considered to be because consumers become more knowledgeable with regard to water management over time. Once consumers become more knowledgeable they become more aware of the potential benefits of water conservation, efforts toward reducing consumption thus Increase.

1.6 Use of the Study for Resource Planners and Policy Formulation

The results of this study can be of use to water resource planners and policy makers. For example the study has shown that the price of water is an important consideration so far as domestic consumption is concerned and therefore impacts demand side management. Demand side management helps in the conservation of water resources and in the improvement of the living environment by lowering volume and pollution loads of wastewater flows. Whilst the price elasticity of demand has been shown in this study to be inelastic in the short-term for all forms of domestic water usage, the price of water was nevertheless important, since it conditioned consumers' water usage behaviour. People of all income levels were shown to take cognisance of changes in the price of water and tended to reduce their water usage as the price of water increased. In quantitative terms, and as noted above, a 10% increase in the price of piped water for residential use in Alberton and Thokoza, the water demand would be reduced by 1 .7%. Such information can be used in cost benefit analysis for determining when or when not to build new water supply investments, e.g. instead of building anew dam or reservoir at some specified early date, price increases can be put in place to delay such an investment which in turn may free financial resources for other development activities such as the improving of water services to the poor.

A legitimate question that can be asked with respect to this study is whether these results can be extrapolated and used by policy makers and water planners in other areas in South Africa with confidence? The answer to this question is that the results of this study can only reliably be used for other areas in South Africa provided the following conditions apply:

- A socio-economic profile similar to that of the study area must exist, i.e., educational level, income level, family size etc.

- The climatic conditions should also closely resemble the study area, i.e., precipitation and temperature, etc. and

- A culture similar to the study area should also exist.

The results obtained are also largely dependent on the implementation of an educational programme dealing with aspects of water usage, i.e. how water is used and knowledge of ways to save water. This then is relevant when attempting to extrapolate these results for other areas in South Africa, as the behaviour of people as the price of water increases, will depend largely on their knowledge of water conservation issues gained from an educational programme.

1.7 Final Comments

This study has shown that water pricing is one of the most important economic instruments that does work for controlling consumers demand for water. Knowledge of people's behaviour under increasing price regimes is therefore an important piece of information for those charged with water policy formulation and water resource planners. CVM has been shown in this study to provide this information in a relatively simple way. As a result of the experience gained in this study it is also suggested that a very important consideration when selecting policy instruments for conserving and managing water efficiently, is the need to act at three levels of intervention for achieving these objectives; these are

- Firstly, national policies and strategies are needed at the macro-level, which set the basis within which the water supply and sanitation industry can operate;

- Secondly, a set of actions is required at the user's level. They can take two forms:

- They may act as incentives for water users who can themselves determine the most efficient and cost-effective water usage patterns. Here Survey No.1 in this study proved to be a useful guide to consumers for doing this; and

- They can be direct regulations that prohibit or limit excessive use of water along with monitoring and enforcement systems, i.e. command and control instruments;

- Thirdly, a set of actions is needed at the utility's level which can act as incentives to affect provider's behaviour on the way they manage the resource. Such actions would of course have to take cognisance of the utilities' own financial health.

The levels of intervention are not alternatives, but instead they reinforce each other. What is needed is a balance of the three layers to create a critical mass and synergy.

1.8 Future Work

In view of the different socio-economic profiles as well as climatic conditions existing in South Africa, it would be of benefit to undertake similar studies to this one in other cities in the country. Use of the experience gained in Alberton and Thokoza should be made in formulating these studies. In this pilot study, undertaken by EPE and discussed in this report, three particular variables only were considered for estimating consumer response for water price increases, these being the impact of family income, indoor and outdoor water use and the water price itself5. It is recommended that in future studies, the variables mentioned above should be increased in number and considered in greater depth. The following list suggets additional variables that should be considered:

- Socio-economic variables of the household itself such as size, age of the members and ownership of the house.

- Characteristics of the residency such as population density , area of the lawn, availability of alternative water sources, age of the house, and water using fixtures;

- Climate conditions, e.g., temperature, precipitation and evapotranspiration rate;

- Water restrictions if any; and

- Type of water service, as measured in number of taps, water pressure, reliability, and water quality.

- In order to successfully undertake similar studies i.e., to estimate the price elasticity of demand for water, in other cities of South Africa, a far wider educational and conservation programme that was undertaken in this study is also recommended. Educational and conservation programmes are used to create awareness of water use and to encourage consumers to change their water consuing habits. Several examples of such a programme have been undertaken in different parts of the world, e.g., Bogor Indonesia, Melbourne Australia and Tucson Arizona, cited in Yepes, Dianderas and Cestti ( 1995, pp. 45-46).

Expanding the number of variables analysed will provide policy makers and water resource planners with a greater understanding of the dynamics of domestic water usage and the factors that influence water users' behaviour under increasing price levels. This will allow policy formulation and water resource planning to be made with greater confidence in an ambiance of consumer participation.

5 In addition, the respondents of the survey were involved In a partial education programme on how they use water and how water could be saved.